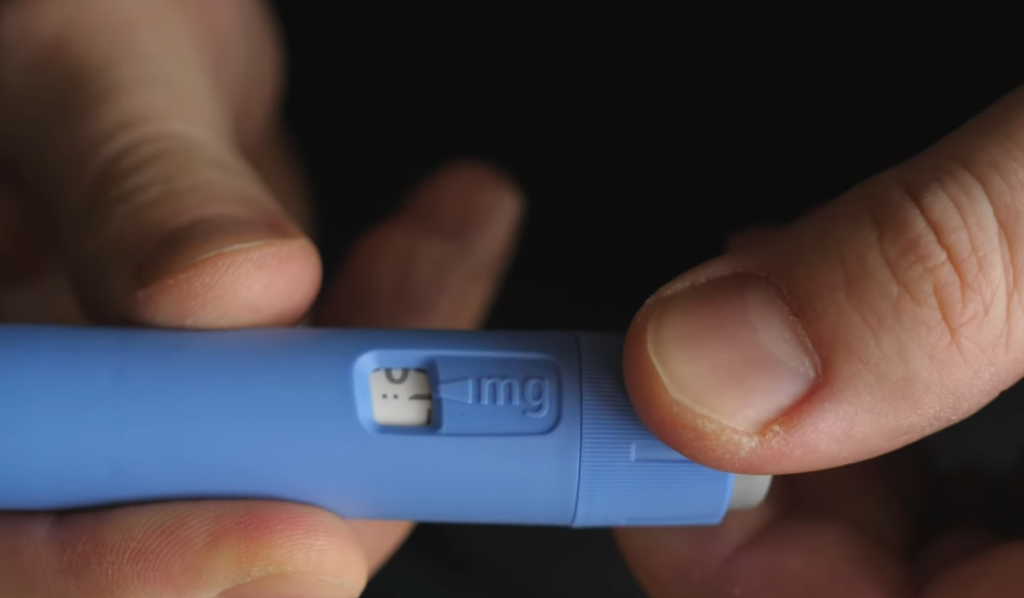

The waiting area of a private clinic in central London, sandwiched between a high-end gym and a cosmetic dentistry office, is remarkably serene. No one appears ill. Most appear impatient. As though giving out jewelry instead of medication, a receptionist carefully places a slim injection pen into a branded paper bag after opening a small refrigerated drawer behind the desk. Perhaps that’s precisely what it has turned into.

These medications, which were created by Novo Nordisk and Eli Lilly, were initially intended to treat diabetes by controlling blood sugar levels and subtly decreasing appetite. Even the pharmaceutical industry was taken aback by what transpired next. Patients started losing a lot of weight—not five pounds, but thirty, occasionally fifty. Demand abruptly increased, reaching far beyond people with diabetes to include a wider range of affluent clients who were seeking control over their bodies—something that predates medicine itself.

However, the reality is different outside of clinics like this one.

Who even considers the option is subtly filtered by the cost alone, which is frequently more than $1,000 per month. It’s difficult to overlook the lack of these discussions when strolling through working-class areas where takeout restaurants predominate over supermarkets. Instead of discussing hormone injections, people discuss the cost of food. Instead of discussing metabolic optimization, they discuss overtime. However, the biology remains unchanged.

It seems like these drugs have made things easier, but only for people who can afford the price. According to clinical trials, patients can lose up to 20% of their body weight, which changes not only their health but also how they interact with others. Different clothes fit different people. Energy gets better. Confidence comes back. As if they’ve found a secret switch, patients frequently express a mixture of relief and incredulity when they describe the change.

But not everyone has equal access to that switch.

Despite the fact that obesity rates were higher among lower-income groups, researchers in Denmark discovered that those with higher incomes were several times more likely to receive prescriptions. The irony remains. Those who could gain the most are frequently last in line, a situation that is hindered by billing rather than biology.

Whether this gap will close or widen is still up in the air.

The change is already evident in corporate offices. When coworkers return from medical leave, they are noticeably thinner, causing quiet conjecture around coffee makers. No one asks outright. However, everyone is aware. It’s possible that these drugs are doing more than just altering health in settings where appearance subtly and quietly affects opportunity.

They might be switching careers.

Weight has long been a factor in salary, promotions, and hiring decisions. If weight loss with pharmaceuticals becomes commonplace among affluent professionals, the benefits could exacerbate already-existing economic disparities. Income is influenced by health. Health is influenced by income. The cycle is getting tighter. It also has an unnerving psychological component.

For many years, losing weight was presented as a discipline test that required routine, self-control, and willpower. It is now possible to chemically modify biology itself to decrease hunger and suppress cravings. Some patients say they feel as though the background noise of their incessant food thoughts has vanished. Others privately worry about dependence and the length of time they will need to take the drug.

because quitting frequently results in weight gain.

Pharmaceutical companies are spending billions to increase production and create newer versions as a result of the increasing demand. Investors appear to think that this category could compete with cholesterol medications in terms of scale, resulting in a steady market of long-term users. Just that belief has changed company values and fueled a covert competition to control what could turn out to be one of medicine’s most lucrative fields.

However, inequality is rarely resolved by markets alone.

Insurance coverage is still uneven; medications for diabetes are frequently approved but those for weight loss are denied. Patients who are financially stranded but technically eligible fall into bureaucratic gray zones. Budgets are stretched by some. Others just give up.

At the same time, cultural perception is changing more quickly than policy.

Talking about these injections has become oddly informal in wealthy social circles, where they are brought up alongside diet and exercise fads. The drugs are still rumored to be out of reach, used by celebrities, and distant in other places. There is a sense that as this develops, the concept of “normal weight” might subtly shift—not because bodies evolved organically, but rather because access did.

Being thin is becoming more and more expensive.

Additionally, it’s unclear what will happen next. Over time, competition may lower costs. Access may be extended by governments. Alternatively, the gap might continue to exist, evolving into yet another subtle layer of inequality that is so ingrained that it seems normal.