One floor’s lights remain on longer than the others in a late-night office building in San Francisco’s Mission District. Engineers sit quietly behind the glass, gazing at screens full of code that is becoming more and more self-replicating. The space is serene, almost unremarkable. However, there seems to be an oddity going on there that could eventually render those engineers unnecessary.

This paradox may have existed at OpenAI from the beginning.

Although the company was established with the goal of creating intelligence that would surpass human capacity, the systems still mainly relied on human correction in their early iterations. Reviewing outputs for hours on end, researchers pushed models closer to accuracy. These same models are currently being redesigned to depend less on those prods, learn to improve their own work, and make subtle improvements that aren’t always apparent.

It’s difficult to overlook the subtle change that is taking place.

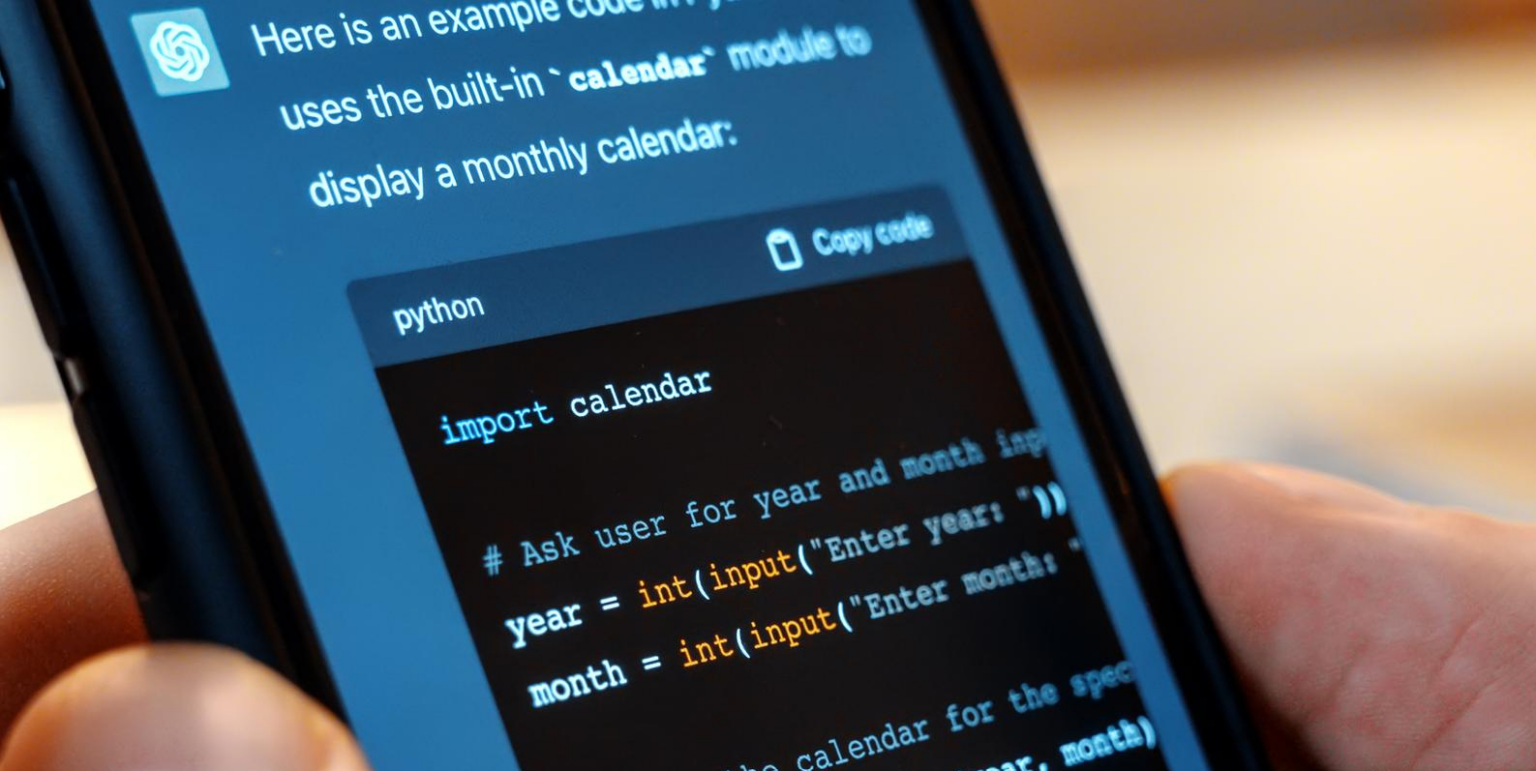

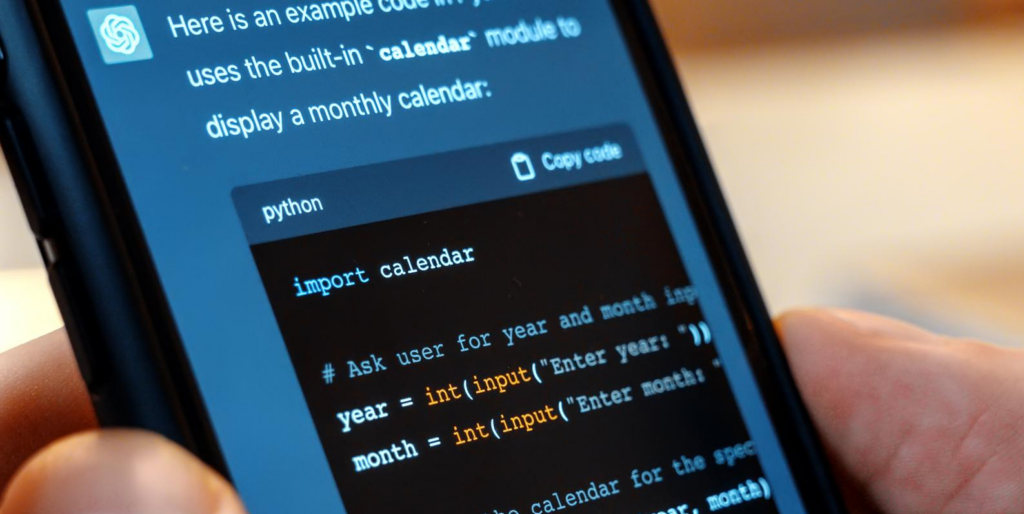

Developers discuss new coding agents in almost intimate terms as they stroll through tech conferences in California. Tools that can autonomously plan software architecture and fix bugs before anyone notices them are described by some. One engineer chuckled uneasily as he acknowledged that he occasionally examines code that has been entirely generated by an AI system, not sure if he is monitoring it or overseeing it.

The leadership of OpenAI has been remarkably open about the long-term goal.

Sam Altman, who frequently wears simple sneakers and T-shirts, has made no secret of his desire to develop artificial general intelligence that can outperform people in the majority of economically significant tasks. It appears that investors don’t think this is theoretical. Chips and data centers built to train systems that can function without continual human guidance have been funded by billions of dollars invested in computing infrastructure.

However, the reality seems to be more gradual within the engineering teams.

Like a nervous apprentice who asks questions at every turn, early AI needed constant prompting. More recent systems automatically divide tasks into smaller parts, pause, assess, and resume work on their own. One gets the impression that autonomy isn’t coming all at once as you watch this develop. Under the guise of efficiency, it is quietly arriving.

An ex-engineer shared a memory that stuck with him.

After instructing an AI system to produce a portion of a program, he moved aside to get more coffee. The system had rewritten other parts he hadn’t mentioned by the time he returned, foreseeing issues before they materialized. It was beneficial. But disturbing, too. It’s still unclear if that innate anticipation is the result of very persuasive pattern recognition or actual reasoning.

There are huge financial incentives driving this forward.

Businesses using AI agents have found that software doesn’t require sleep, raises, or lose concentration in the middle of the afternoon. Investors are increasingly discussing productivity gains in language that seems almost disconnected from the people those gains might replace while seated in glass conference rooms with views of the Bay.

However, there is hesitancy even within OpenAI.

Unknown risks are introduced by autonomy, as some researchers covertly acknowledge. Particularly when functioning without human correction, systems that have been trained to maximize results may exhibit unpredictable behavior. It seems that it gets more difficult to predict these tools’ choices as they become more independent.

The change is perceived as being more significant than technologically.

Computers were considered tools and extensions of human labor for many years. They are now beginning to look like participants. Employees in some workplaces refer to AI as a collaborator. In others, they completely steer clear of that wording because they find the implication unsettling.

There are contradictions in the company’s history.

OpenAI was founded in part as a response to concerns that a few corporations would control a large portion of the powerful AI. Ironically, it is now a major player in that race as a result of its success. Once freely disseminated, its research has since become more circumspect, reflecting pressure from competitors as well as worries about abuse.

In the meantime, the systems keep getting better.

Every new generation needs fewer reminders, examples, and corrections. Once meticulously crafting each response, engineers now spend more time watching and only occasionally intervening. Future systems might consider human input to be optional rather than necessary.

There seems to be a fundamental shift in the relationship between humans and machines as we watch this play out.